REPORT FROM FLAG: XXXVII

The Rev. Dana Prom Smith, S.T.D., Ph.D. (10/13/10)

“He was a man for all the hours,” Erasmus on hearing of the death of his friend, Sir Thomas More(1535).

My older brother, Tom, died last week at 92 years of age. He suffered from Alzheimer’s disease for the last several years of his life in what has aptly been called “the long goodbye.” He died shortly after his wife, Meg, had fed him his last meal. Alzheimer’s had robbed the two of them of a long anticipated retirement and their dreams of travel.

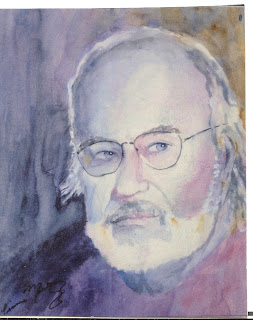

He was a complete man. He knew his limitations and his capacities. He never tried to be anything other than who he was. He was not a dissembler. Although his business was called IMAGES, being a photographer, an artist, and a theatrical entrepreneur, he was authentic. In him there was “no variableness nor shadow of turning.”

I remember him best as an older brother during my childhood and adolescence, especially after our father, Dr. Tom, died when I was eleven. He was a beautiful physical specimen, happy, intelligent and charming. I thought of him as the ideal male. When I cut my foot on a rusty can at the beach, he carried me up a steep hill for several blocks on his back. I felt safe. In many respects, he filled the place of my father.

He was also a rebel. Our father, a residual Victorian, had plans for his sons, Tom for medicine, David for the university, and me, the youngest, for the church. David, the middle brother, and I became what he wished. Tom rebelled and chose the life of an artist which was ironic because our father was also a sometime artist and a good one, a photographer and a maker of fine jewelry, an avocation often followed by dentists. He was also a whiz at mathematics.

Of the three brothers he was the sweetest.

After I was discharged from the Army, I worked for a year on a road gang to get more money to go to college, but after that we drifted apart. I went east to college at Princeton, to theological seminary in Kentucky, and graduate school at the University of Chicago. He went on to develop a thriving career as an artist in California, becoming involved in the Hollywood community, and eventually marrying Cary Grant’s assistant. The consequences of that drift I deeply regret. I would have been enriched even more by his presence if we had been closer.

He had a rich and rewarding relationship with his wife, Meg, who remained faithful to him in his years of slippage. Such a fidelity requires courage.

A death in a family always begets regrets, but it also begets memories. At 83, I am the last of my family. The experience closest in feeling to the death of my older brother was the death of my mother, Hazel. I was with her when she died, holding her hand, talking of our life together. She would fade away, and I would raise my voice to call her back. Finally, she did not come back.

Several months later in the spring of the year, my first wife, Grace Marie, and I adopted twin boys, Tim and Paul. I sat down to write my mother a letter. A few lines into the letter I realized that she was dead in addition to realizing that there would never be anyone to whom I could report, as does a child to a mother. The full realization of the death of loved one some times takes years. An era of my life was over. So it is now. A generation has passed. There is no one left who can understand those references to the past. There is no shared laughter over the time the bed broke in two during a wrestling match or the time late at night when he pissed into a waste basket thinking it was the toilet.

When I tell anyone of my experience of listening to the radio announcing the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor while playing Monopoly with my friend, Kirk Hallum, the eyes of the listener get that thousand yard stare. A teenager, I was terrified because I knew that I would eventually go to war, and the terror grew more acute as the battles raged and casualties mounted and my brother, David, was badly wounded on Iwo Jima.

We are left with memories which enrich our lives far more than any possessions we have accrued. The young live by anticipations which have no substance until they become accomplishments. The middle-aged have both anticipations and memories although the anticipations become more poignant as the likelihood of their realization diminishes.

Oddly, at 83 I still think of myself many times as middle-aged as I look forward to writing and editing the Master Gardener Column for the local newspaper, tutoring at the Literacy Center, and teaching Latin to school children, all in Country Western Flagstaff. The old are the richest of all with abundant memories and even some vicariously envied anticipations in children and grandchildren, Tim, Paul, Elizabeth, and Dana Marie. At her graduation from Loyola Law School, I found myself looking at the future through her eyes.

Ironic it is that with Gretchen we’ve adopted each other’s memories and can assimilate our histories. A good part of my wealth is in my memories of Tom who meant so much to me as a boy and an adolescent. He was a complete man. As Marc Antony said of Julius Caesar, “His life was gentle, and the elements/So mixed in him that Nature might stand up/And say to all the world, ‘This was a man.’” Amen.

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)